Our Portable Heritage

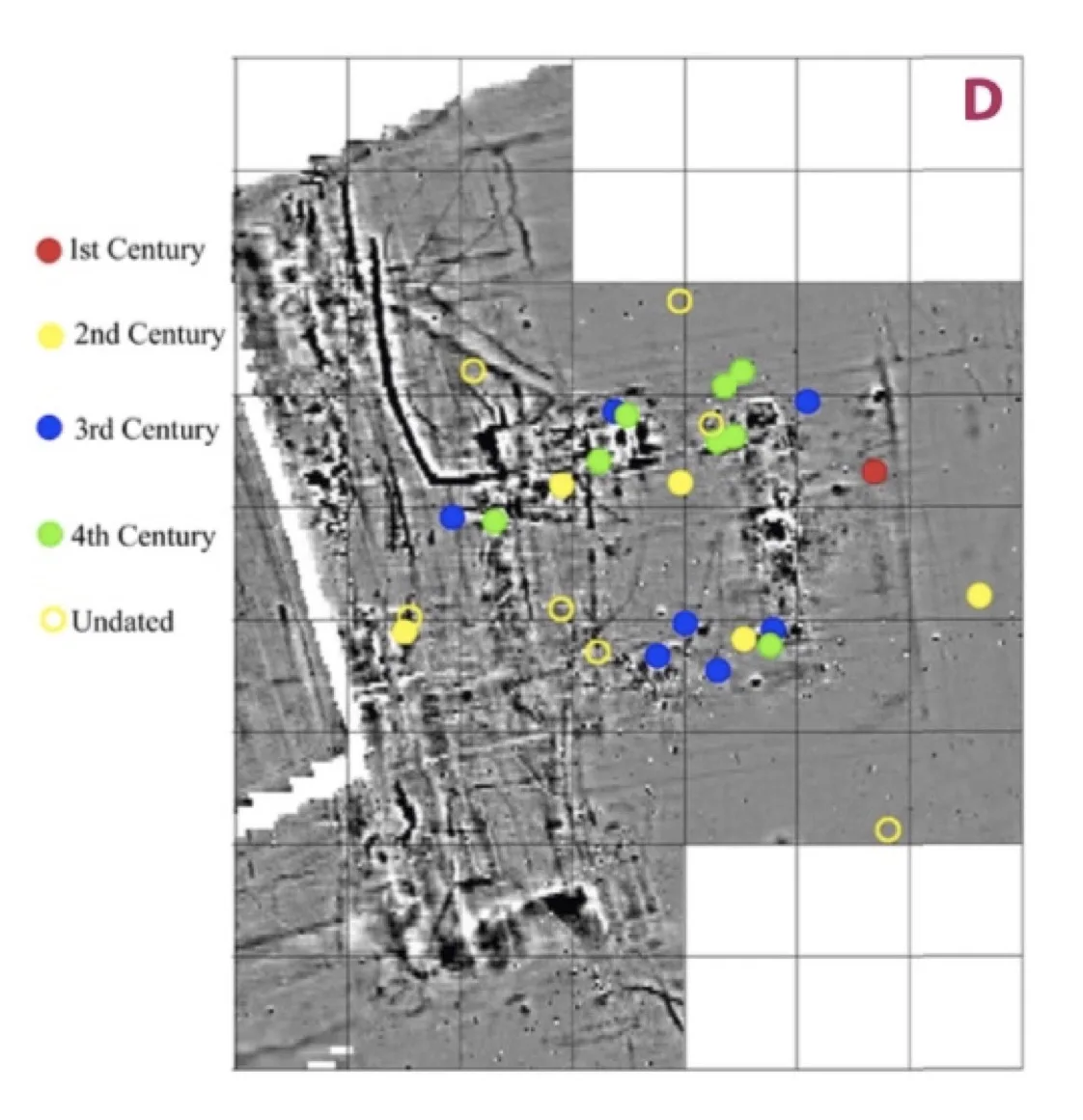

Portable antiquities, including small finds like coins and artefacts that can be removed from archaeological sites, are vital material remains of past human activities and integral to the archaeological record. These finds vary in importance: some provide crucial dating evidence within stratified layers, enhancing our understanding of subsoil deposits, while others, found in topsoil or plough horizons, contribute to our knowledge of the contextual landscape.

Fieldwalking has long been used by archaeologists to collect surface finds and assess the archaeological potential of an area, predating the invention of metal detectors. It remains a valuable systematic survey method, even as metal detectors have become more commonly used. However, it is not uncommon for commercial archaeology sites to strip topsoil without conducting any prior artefact survey.

Considering the impacts of construction development, agricultural practices, agri-chemicals, and the potential loss of information from unrecorded finds by metal detectorists, the question arises: How much of our archaeological heritage has been lost in recent decades? Is it 25%, 50%, or even 75%?

ALGAO: The Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers is keen to support your initiatives. We see the proposed training courses as a way of embedding metal detector use into professional practice. It will be particularly important to include clear understanding of archaeological evaluation and mitigation recording in the planning process, and to ensure that detectorists working in these projects work to a clearly defined specification, such as you have outlined, to support the aims of the project. ALGAO can certainly help with support and guidance on this aspect, spread awareness of the training, and encourage the use of standard specifications among our members.

The Federation of Archaeological Managers and Employers (FAME) welcomes the intention to set up an Institute of Detectorists. We support the principle of a regulatory body to educate and influence the behaviour of metal-detector users and requiring adherence to the Code of Practice and archaeological principles.

Chris Gosden, Director, Institute of Archaeology.

Metal detectorists are one of the largest groups of people in Britain engaged with archaeology. People detect for many different reasons, but people often search land they know well and can use that knowledge to predict where archaeological finds might occur. The Detectorist Institute & Foundation proposes to engage systematically with the detecting community to provide training, but also to exchange knowledge about landscapes and finds. This is a much needed initiative which is being developed on extremely sound principles.

A detectorist-led Initiative. As the archaeological record diminishes, the popularity of metal detecting as a hobby or ‘sport’ is on the rise, with estimates suggesting there are now over 40,000 active metal detectorists. In contrast, only about 3,000 individuals actively record their finds. Considering that merely 6 to 7% of detectorists contribute to record-keeping, one must question whether the archaeological record is truly being respected as Britain’s incredibly rich source of historical information to be treasured.

The DIF was established in recognition that our portable heritage, along with the contextual information gained from its discovery, is rapidly diminishing. In prioritising heritage conservation, the DIF wants to encourage more metal detectorists to understand and support our aims, based on the relationship between searching for historical artefacts and making a positive contribution to heritage conservation.

Furthermore, despite the conservational challenges posed by commercial archaeology, such as time constraints, financial limitations, and contractual obligations, there are organisations that support integrating detectorists into archaeological teams and incorporating metal detecting into professional practice

The Only Way To See – The Harris Matrix 06/10/2018

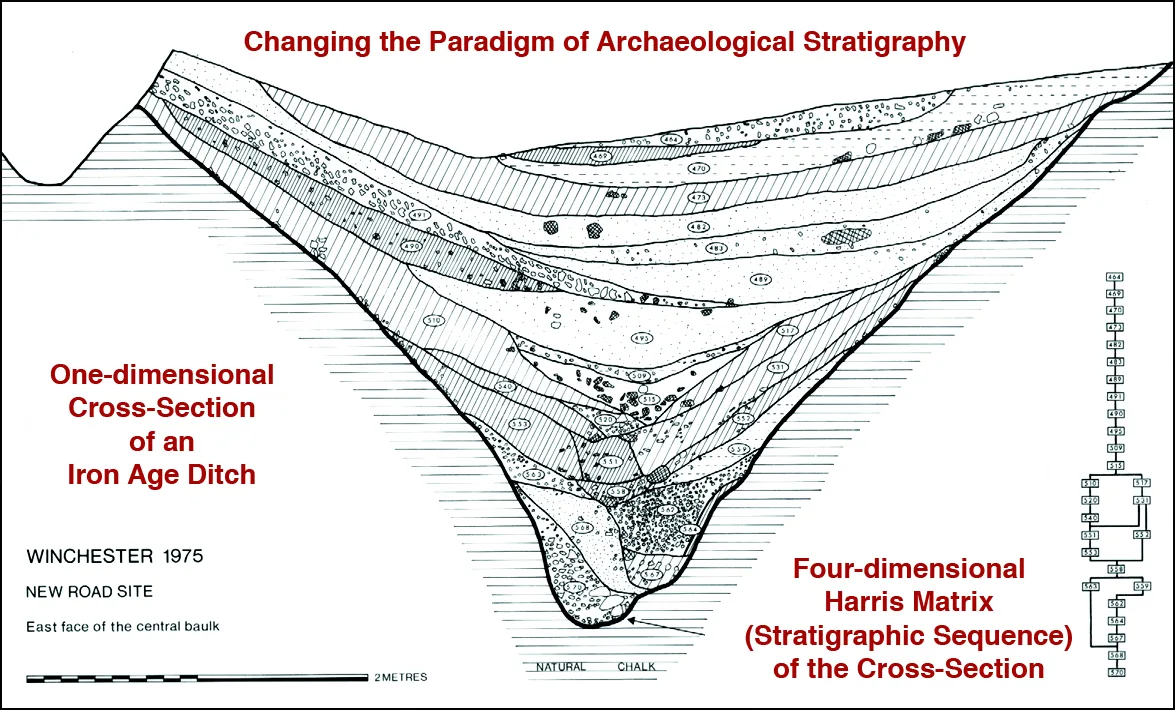

Any excavation in the earth involves the disturbance of stratification. Without proper recording, that digging results in the loss of the topographic history of an area through the destruction of surfaces and the inability to construct a ‘stratigraphic sequence’ for a site.

Such a sequence, seen by way of a Harris Matrix, is indispensable to all later analyses of the site and the objects found within it. Thus, the teaching of stratigraphic methods is crucial for all who investigate and search for the Past by excavations of any size, or any place.

I commend the efforts of the Association of Detectorists and the University of Oxford to bring together archaeologists and metal detectorists with a course that includes vital discussions on the stratigraphic method in archaeology—the only way to dig and more important, the only way to record the buried remains of history.

Also to be commended is the possible establishment of a professional Institute for Detectorists, so the stratigraphic approaches to archaeological sites becomes the industry standard. Many archaeologists still use non-stratigraphic means effectively to dig holes into History, but Britain has led the way in correct stratigraphic excavation and recording methods. It is therefore heartening to see that many detectorists wish to engage in such professional methods, which will enhance their work and are fundamental to any disturbance of the earth.

Dr. Edward Harris MBE FSA